From Scale to Purpose? The EU and its support for European tech startups

As the global race for tech dominance intensifies, the EU has shifted gears to support its homegrown startups. Yet creating European unicorns that can compete with the US and China will require bigger thinking than the EU can currently muster. So why not play to its true strength, by using technology strategically to help solve its social and environmental challenges?

Bold thinking – yet out of reach

As China rises and the US wavers, the European political debate is awash with terms such as “strategic autonomy”, “digital sovereignty” and “innovation made in Europe”. And ever since European tech companies seem to be catching up with their US competitors, European political leaders have begun to express new ambitions for homegrown tech sectors.

Take French President Macron, for instance, who argues that Europe must switch from its 70-year-old “catch-up economic model”, to instead “lead the digital transformation through radical innovation”. Such bold assertions are in line with Europe’s trend of geopolitical self-assertion with respect to the US and China.

Suddenly, then, European startups find themselves in the midst of a new global battle conflating economic interests, new technology and political ambitions. Their apparent new role is to grow quickly into the new European “Digital Champions” called for by ambitious politicians.

A closer look at the European startup ecosystem, however, reveals a paradox. Europe boasts a long tradition of successful research and innovation. And European economic integration offers the prospect of a single market that should be able to compete globally. But the European startup industry appears underdeveloped compared to its global competitors – despite an explosion in the number of companies setting out to conquer new markets over the last decade.

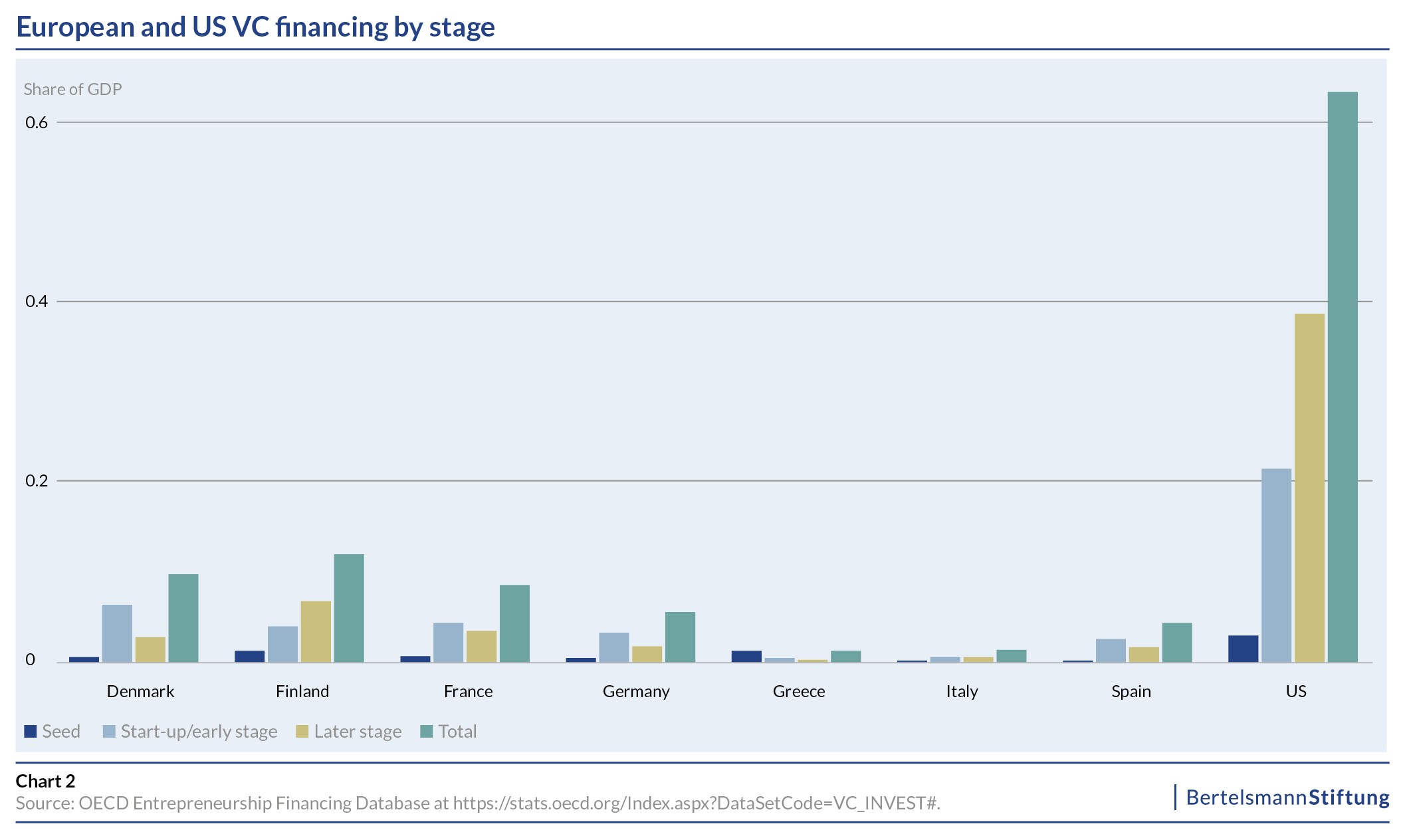

One simple reason for this stands out. While US startups have received $1.2trn in Venture Capital (VC) investment since 1995, the figure for Europe, at $200bn, is six times lower. Optimists point out that Europe is catching up: Its VC-market has grown from 4% of the global market in 2004 to 15% in 2020. And European VCs raised record amounts of new funds in 2020. What’s more, a remarkable 38% of global seed stage capital – that is, funding for the growth-phase – is raised by European startups.

The crucial figure, however, is this: while Europe’s startups raised more than a third of early-stage capital, the funding raised by scaleups – that is, companies aiming to grow – declines sharply to only 9% of so-called “mega-rounds plus”, where funding is beyond $250m. Instead, 50% of such rounds came from the US and almost 40% from Asia.

In short, pretty much every successful company emerging from European universities and startup-ecosystems is destined, sooner or later, to leave the continent. This has a direct impact on Europe’s global standing – by harming its competitiveness, employment, tax base and indeed the growth of its innovation ecosystem, which relies on virtuous feedback-loop

The EU joins hands with the sector – but the gap remains

Unsurprisingly, then, the issue of funding is central in the most recent demands formulated by European startup associations, restated succinctly in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and – for the first time – aimed directly at European policymakers.

Regarding investment and finance, associations call for a “multi-tier plan to unleash private funding, especially the VC sector”, and for an “increase in public funding”. Regarding the crucial issue of late-stage funding, they recommend that the EU create “a tech buy-out fund to accelerate direct and indirect shareholdings in strategic sectors for Europe, such as health, cybersecurity, Artificial Intelligence (AI), quantum computing or blockchain”.

Following intense consultations with the startup sector, the EU is doing its best. The newly designed European Innovation Council (EIC), for instance, began making direct equity investments into European tech startups in January 2021 – a groundbreaking development in the EU’s innovation policy. The EIC fund will have the capacity to inject €3.5-4bn into the market by 2027 and hopes to attract a further €30-50bn in private investments. This would contribute to reducing the gap in VC funding between Europe and the US.

And the EU is doing more – InvestEU, the bloc’s guarantee programme for European SMEs, will also provide additional support. In theory, this means that the European Commission could become the owner of a future European Google.

In the long-term, however, the lack of large-scale financing in Europe means that the probability of European-bred companies being bought by – most likely – American VCs will remain as high as ever.

One of the key differences between the US and European capital markets is the fact that institutional investors play a much larger role in providing VC in the former than in the latter: more than half of the nearly $160bn fund raising in the US between 2012-16 came from institutional investors compared with just over a quarter of the nearly $50bn raised in Europe over the same period. Pension funds make up a large part of these institutional investors, reflecting the fact that funded pensions play a much larger part in retirement income in the US compared to Europe. These profound structural differences make it difficult for Europe to generate the private-sector savings required to support significant VC activities. The problem is exacerbated by regulatory differences.

So even the achievement of more modest goals – such as a degree of control over strategically relevant tech industries – would require much larger funding structures at European level. The obvious answer is the creation of a European Sovereign Wealth Fund. Indeed, plans for such an entity are reported to circulate within the European Commission under the title “European Future Fund”, with a view to investing European public money into sectors deemed strategically important.

However, such a fund quickly ran into political resistance and did not make it into the EU’s 2021-27 budget. Instead, the European Investment Fund (EIF) is now testing the waters for a Pan-European Investment Platform for European Digital Champions to invest in growth stage VC firms which in turn invest in the pre- and post-IPO segments of European tech startups – a compromise, given the political obstacles towards going full-throttle ahead.

The measures set out by the EU are in many ways pioneering. Yet in their present state they are unlikely to fulfil the bloc’s ambitions of digital sovereignty. One observer puts it into a nutshell: “It’s like setting up a Michelin Star Restaurant, but instead of developing a full menu, you focus only on high quality starters. Don’t be surprised if other restaurants buy your starters and you end up a caterer.”

A different way forward? Paradigm shift required…

If digital champions in the traditional, US-inspired sense are out of reach, where could Europe head to instead? Interestingly, a closer look at the reasoning behind European policy-makers’ new tech rhetoric suggests that such ambitions are fueled more and more by the realization that disruptive innovation is required to solve the long-term social and environmental challenges faced by Europe and beyond.

Such “purpose-driven” approaches to innovation are in line with broader – and increasingly strident – calls emanating from various civil society initiatives to include “mission” or “impact”-oriented outlooks systematically in both public and private-sector activities. In practice, this means that objectives are clearly stated and results objectively measured.

This perspective is gaining ground in policy circles, at least rhetorically: virtually all EU-initiatives in support of startups and indeed innovation as a whole are branded politically as cornerstones to achieving the Green Deal or, more broadly, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which the EU supports.

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified this focus, with funds strategically channeled into the biotech-sector to create a vaccine being the most obvious example of such a “purpose-driven” approach to fostering innovation. Incidentally, the breakthrough was achieved by BioNtech, a European startup that is listed on the US’s Nasdaq.

This would mean that the dimensions of mission- and impact-orientation become built-in features at all levels of both policy-formation as well as when it comes to financial assessment and reporting frameworks. The tools required for such a paradigm shift are increasingly in place. Regarding policy, the European Commission has sought advice from leading independent experts on mission-led policy design in the context of Horizon Europe, for instance – and, what’s more, implemented the recommendations.

Regarding financial assessment and reporting standards, the most interesting breakthrough could be found in the field of accounting. “Impact-weighted accounts”, for instance, constitute an advanced technique for shedding light on the entire performance of companies. These enable investors to apply traditional methods of analysis to a broader set of comparable data which, crucially, includes a company’s ability to achieve its stated mission. “Net impact”, then, can be determined and quantified with respect to broader goals, such as those of the EU’s Green Deal or the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Ideas for a paradigm shift in global financing systems designed to achieve global missions, such as the SDGs also exist. Niche areas within global capital markets, such as impact investing, are experimenting with purely purpose-oriented finance. But there remains a long way to go for such thinking and acting to become mainstream. And, of course such a shift towards purpose has its own funding challenges.

In the meantime, the EU would do well to push for purpose rather than search for scale in developing the European startup ecosystem. In doing so, it would make a virtue out of necessity by playing to Europe’s comparative advantage, as visions of digital sovereignty via “Digital Champions” remain elusive.

Tools and instruments for a mission- and impact-oriented paradigm shift in both policy and finance are increasingly available. For it to occur in full remains a matter of political will.

Kommentar verfassen